Pattern grading can be done in a variety of ways–slashing and spreading a pattern, shifting points as x,y coordinates on a grid, radially, and I’m sure there are more. If you have a sloper that fits you well, you can use your sloper as a guide when grading patterns to your desired size. Using a sloper to grade is essentially using the slash and spread grading method, but the approach is a little bit more hands on and intuitive than it is mathematically precise.

Someone asked me for advice on how to use a sloper to grade patterns, so I wanted to write out the process as I would approach it. This is only one way among many, but I hope that it might be helpful and maybe help clarify working with slopers to adapt sewing patterns to specific measurements as well.

What is a sloper versus a regular pattern?

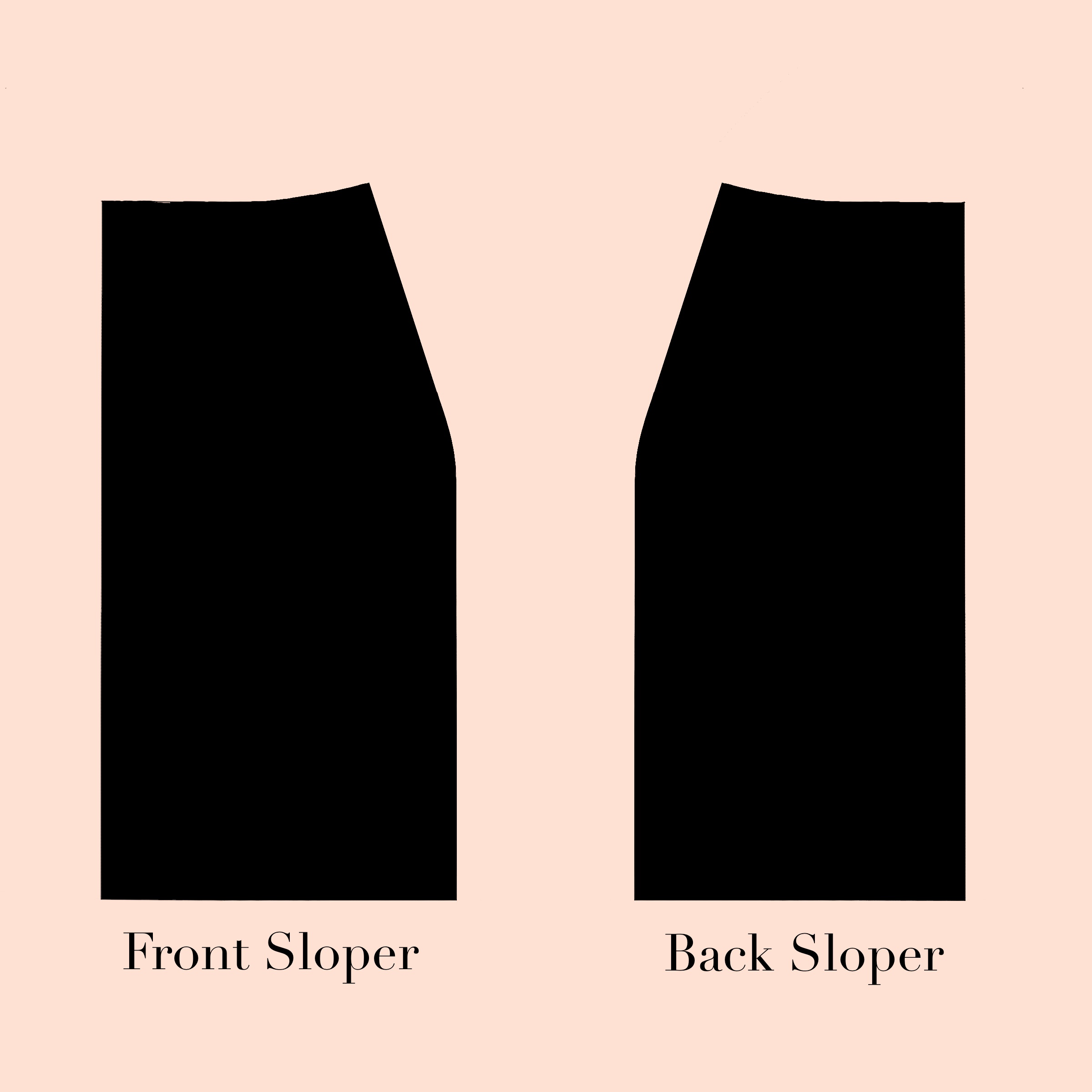

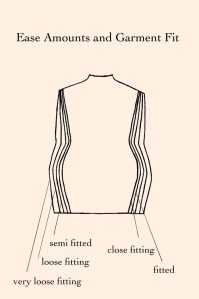

A sloper is a basic fitting shell, or a pattern that has been adjusted to fit your body shape very closely, with only the minimum required ease to allow for movement (wearing ease). A sloper represents the minimum amount of fabric required to fit your body. A sloper pattern that has been adjusted to your body is like a two dimensional dress form, a map of mass distribution and fitting adjustments to accommodate them. A fitting shell or sloper pattern that has not been fitted to a specific body is a pattern that fits a generalized ideal body as closely as possible while still allowing for movement.

A pattern is different from a sloper in that it doesn’t follow the body exactly. It almost always adds fullness or additional ease in a variety of ways to the garment in order to create shape. There are places where the garment must anchor to the body or be held in place by clinging close to the body, and in those places, the sloper and the pattern will be almost identical. But in other areas, the pattern will add extra fabric to create volume.

How can a sloper be used to work with patterns?

A sloper provides you with a map of the minimum amount of fabric necessary to fit your body. You can overlay and compare this to the pattern to be sure that the pattern is large enough to encase your body effectively. If there are places in the pattern that are smaller than your sloper, you know that you need to deal with those and add room in some way before you ever cut into your fabric.

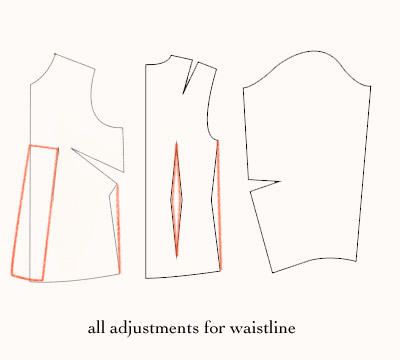

A sloper can also help you to make your standard necessary adjustments to the pattern before you test, and can save a lot of repeated steps and fitting processes if you sew a lot of your own garments. If you know that you always need to increase waist circumference to get a good fit, you can incorporate this adjustment into your sloper and know where to add to every pattern you make before you begin.

A sloper can be used to grade a pattern up or down to your desired size as well, though this method may be less precise than grading by more mathematical methods. Essentially, using a sloper to grade is just one way to do a slash and spread grade, and the sloper becomes a guide for moving pattern pieces. It offers a quick and painless way to adjust patterns visually, and it can save some time by incorporating your fitting adjustments and resizing your pattern in a single step.

What is slash and spread grading?

Pattern grading is the process of enlarging or reducing pattern dimensions to create different pattern sizes from an existing pattern. This can get very complicated, because the way the body varies from size to size is a complicated subject that garment makers and manufacturers continue to struggle with. But the idea is simple enough.

Overall grade = the difference between the current pattern measurement and the desired pattern measurement (body measurement plus desired ease).

Distributed grade = the overall grade amount divided by 4, which tells you how much to add or subtract to each quarter panel of the pattern. Pattern pieces generally represent one quarter of the body, unless they’re asymmetrical, so 1/4 of the overall grade amount is distributed to each piece.

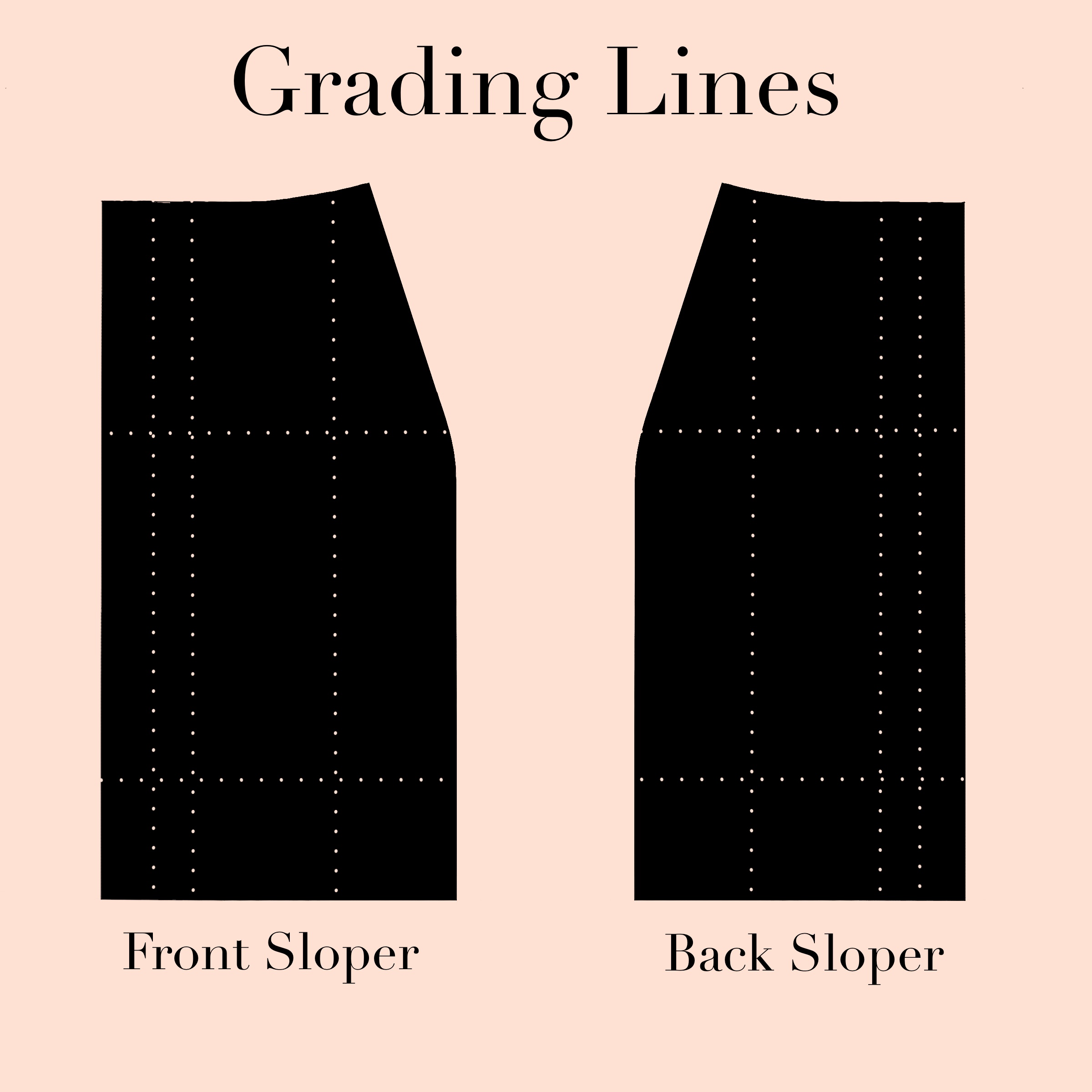

This additional space is added to the pattern in specific places to allow for the different amounts the body grows or shrinks from size to size and different places in the body. (For example, when increasing a size, you may add two inches at the waist, but the neckline circumference will increase by much less.) There is a standard set of grid lines representing where to slash and spread or overlap a pattern.

If you’re grading without a sloper, these slash line placements are very precise so that you can grow the pattern a very specific amount exactly where it needs to expand. That’s why there are double lines at center front and back. There’s a really good Threads article that explains this in detail here:

www.threadsmagazine.com/2008/11/01/quick-reference-for-cut-and-spread-pa…

So how do you determine where exactly to slash a pattern for resizing? It depends on your purposes. If you’re grading a pattern to an abstract standard, a generalized pattern to be used by multiple people and body types, you can use the standard grid lines shown above. These do seem to be agreed upon somewhat universally in all the patternmaking sources I’ve seen that use a slash and spread method.

But if you’re grading for your own body measurements or a specific person in mind with specified proportions that may or may not align with sizing standards, then the slash lines positions are more flexible and are determined by the needs of those body dimensions.

The exact slash line placement can vary based on pattern complexity as well. In patterns that aren’t very complicated like a skirt, the cut lines to slash on can be positioned with less precision than a more complicated pattern with crotch curves and scyes to deal with. The multiple slash lines are really just to allow the pattern to be spread or overlapped smaller amounts in more places so that the change in volume is spread out. In a pattern like a skirt with very simple lines, changing it incrementally by adding or subtracting smaller amounts in more places would yield the same results as fewer slashes that add or subtract a greater amount in fewer places.

Sloper Versus Pattern for Grading Purposes

If you’re using a sloper to grade rather than precise mathematically determined slash and spread amounts, this changes your approach in a couple of ways.

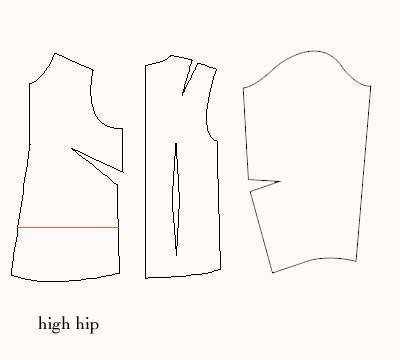

In terms of slash line position, if you’re grading with a sloper, especially one that has been adjusted to fit your body specifically, you usually only need to slash and spread where your body needs the space or where the pattern needs to lengthen. For example, if you’re making vertical adjustments and you have a waist to hip length that is shorter than standard, then your sloper hip and waist position are what you should use to determine whether or not you need to adjust the pattern. If the pattern has too little or too much length from waist to hip, then you would slash between the waist and full hip and move the pattern to line up with your sloper. The exact placement of the slash line doesn’t matter as much as the correct positioning of body landmarks.

It’s also slightly different than straightforward slash and spread grading because wearing ease and body measurement increases are already incorporated into the sloper pattern itself. The design ease is what will need to be added to the sloper. The final pattern and the sloper should not match exactly, because the sloper represents minimum fit and the pattern represents style created using volume and seaming. The goal is to preserve the proportions of the pattern while using the sloper to adjust sizing.

It is important to note that while wearing ease (included in the sloper and in patterns already) is somewhat universal, design ease, which is the widely varying amount of extra room added to create volume in garments, is proportional. For a style to have the same overall appearance whether a size 4 or size 16, that amount of additional volume must increase proportionately relative to the body. For example, having 2″ inches gathered in at the waist will appear differently on a waistline that is 24″ than a waistline that is 40″ in circumference. Two inches represents about 8% of the waist circumference in the original pattern. For the style to be graded well, the proportions must be considered where there is fullness added to the pattern. For it to appear proportionately similar, the amount gathered for a 40″ waist would need to be about 8% of the waist circumference, approximately 3.3″.

If you are grading up or down a size or two, especially if the garment design is simple, you may not need to worry about the proportions changing too much and you can probably disregard it without your end result being disproportionate. If the pattern is only going up or down in size by a couple of inches, the additional percentage of design ease to factor in is small enough to be negligible. But for greater size increases or decreases, it’s advisable to consider the proportions of body measurement compared to the pattern measurement and keep that proportional relationship consistent in your graded pattern.

How the Garment Hangs from the Body

When using a sloper to grade a pattern, consider where the pattern aligns most closely to the shape of the body, and where it hangs from or anchors to. For skirts and pants, the place the pattern anchors on the body is usually the waist and hips. The design relies on closeness to and tension against the body to keep it in place. In these places, the pattern should be most similar to the sloper. If the garment has pleats or gathers at the waist, there will be additional volume there, but aside from design elements, the pattern will take the shape of the body there, for the most part, because it anchors there.

Similarly, ignoring the cut away shapes of the neckline and the embellishment of the collar, the area where shoulders, neck, and back intersect at the top of a pattern is usually almost identical to a sloper. This is the part of the body that the garment hangs from, so a smooth, close fit to the body can be expected here (with the exception of shaped collars or funnel necklines, etc).

For the simple flared skirt I will be using as an example, the garment anchors at the waistline, and uses tension against the body here and the size difference between waist and hips to remain in position. So my sloper and my graded skirt pattern will have the same shape here, because there are no design features and no design ease. If there were design features like pleats or gathers, I would figure out the proportions they represent relative to the body, and figure out the amount to add or subtract to the graded pattern in proportion to the desired body measurements.

The Grading Process

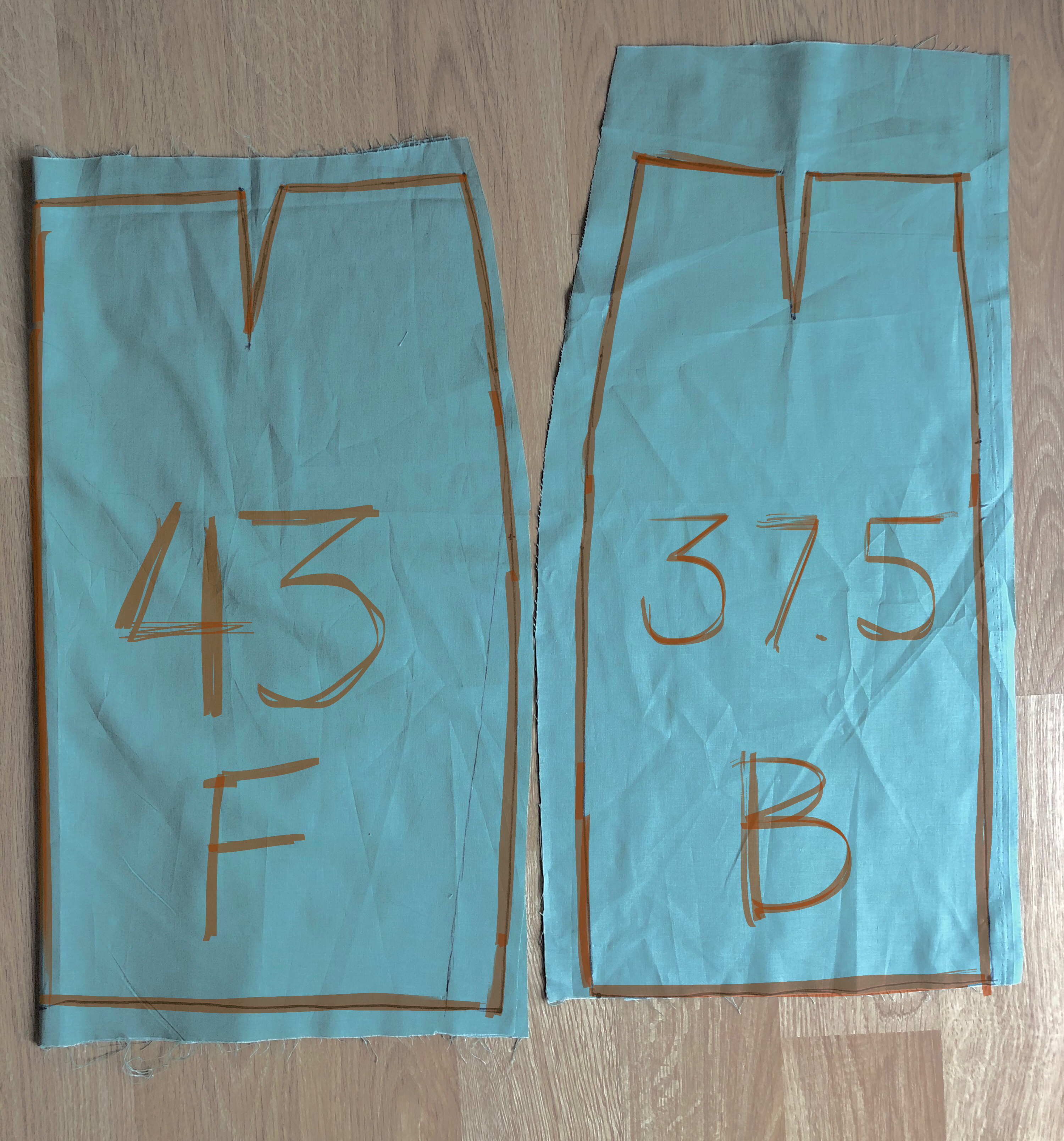

To grade a pattern up or down with a sloper, you’ll need a sloper in the desired size, and a pattern that you want to grade, as well some large paper to trace on, sharp or mechanical pencils, a ruler or square, scissors, and probably some scrap paper and tape. It’s best for these purposes if your sloper extends the full desired length of the finished pattern. For my example, I’m grading a skirt pattern, so my skirt sloper should extend to the desired length of my final pattern. If needed, extend the vertical length at the center front, center back, and side seam lines.

Begin by tracing a copy of the pattern you want to grade. For simplicity’s sake, leave off seam allowances. They can be added back later and it’s much less confusing to remove them for now. Markings and grainlines aren’t necessary either, just the pattern shapes and structural features like darts and gathers or pleats. Facings are unnecessary as well, and can be redrafted from the final graded pattern.

Slash and Spread Along Grading Lines

Typically for the slash and spread method of pattern grading, a standard set of gridded lines is used to determine where to slash the pattern and by what percentage of the desired grade the pattern is to be expanded or reduced. With a sloper, the precise distance to move pattern pieces can be determined by just aligning the pieces visually, though for patterns with a lot of additional volume, this just establishes the basic shape.

It’s important to remember that additional volume may be needed where there is a lot of design ease added to the pattern so that you can preserve the proportions. But sliding the pattern to align with the sloper provides a starting point, and for small size changes, the proportions are similar enough that they can sometimes be ignored. For my simple flared skirt example, the flare at the bottom is the only place where the design ease proportions are a consideration. If my original pattern has a bottom hem that is 12″ larger than my sloper hem of 36″, then the design ease is 12 divided by the sloper measure (or body measure plus wearing ease of 36, for a result of 33%. So whether I’m grading up or down, the final pattern should be 33% larger than the body at the bottom edge.

So start with the grid lines. If your pattern has seam lines that divide each quarter into pieces, these grid lines can be moved slightly to position them within pieces. This is more of an eyeballed art than a science. There is less flexibility in locations like the neckline or scye, though. If it helps, patterns can be butted up to one another at the seams, temporarily taped and separated later.

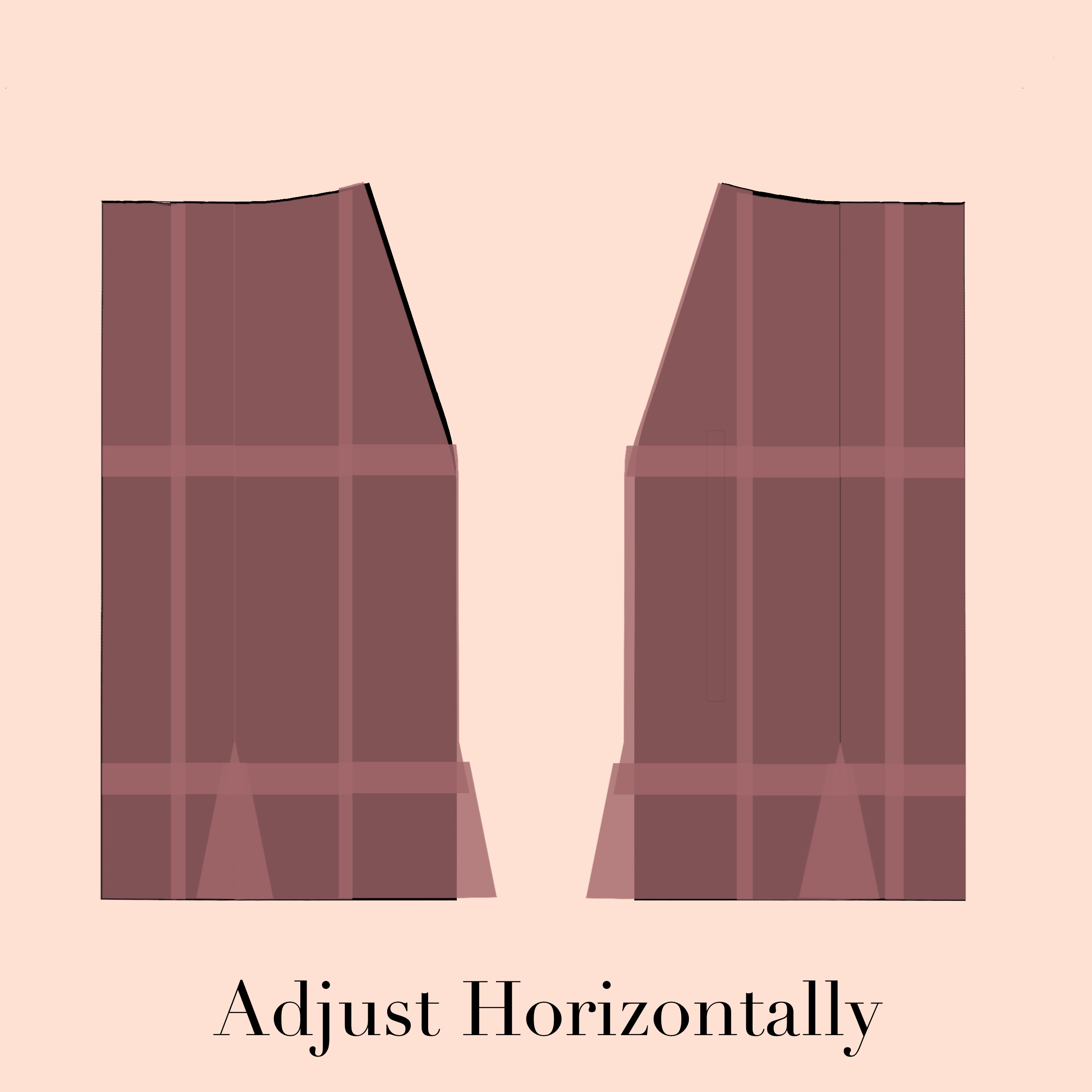

Align the pattern with the sloper at the low hip. (This is my preference, generally – using the unchanging hard skeletal structures of the body at the full hip and the high bust to choose pattern sizing and as a starting point for adjustments.) When sliding pattern pieces, try to keep them aligned with the XY grid formed by the center front and an imaginary line bisecting it at a 90 degree angle. The pieces will be moving vertically and horizontally, but shouldn’t be tilting.

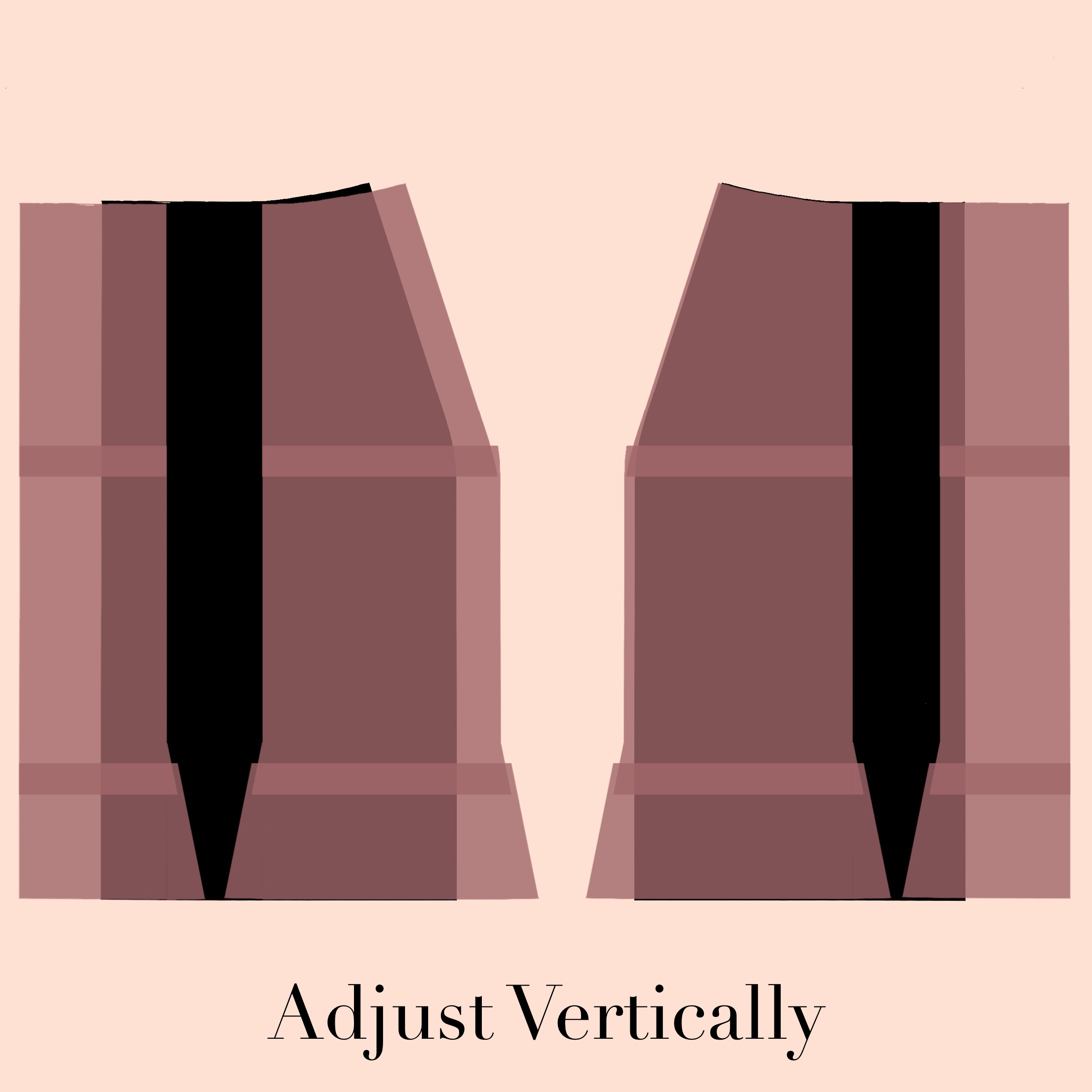

Adjust horizontally first. Cut along the horizontal grid lines and spread or overlap pieces to align to the top and bottom of the sloper. Keep the low hip of the pattern in alignment with the sloper low hip. It can be helpful to tape the pieces in place temporarily and to use scrap paper to tape and stabilize pieces in place when spreading them apart. The new position of the pattern top and bottom will be used to redraw your graded pattern.

Then adjust vertically. Cut along the vertical grid lines and spread or overlap pieces to align them to the inner and outer edge of your sloper pattern. Tape into place. The new position of the pattern pieces will be used to redraw your graded pattern.

Redraw the pattern seams, smoothing and stretching or condensing curving lines as needed. True the front and back by making sure that side seams match up lengthwise. If the original pattern is symmetrical at the front and back side seam, the graded pattern should be as well.

Use the new pattern seamlines as a guide to redraft any attached facings, facings, or waistbands to fit the new pattern shape. Redraw seam allowances if desired.

Grading a Pattern Up Using a Sloper

Here is an example of how I would approach increasing a pattern in size. Let’s say I have a stretch pattern for a flared skirt that is a few sizes too small, but I have a sloper that is my desired size and fits my measurements.

First I trace the pattern onto a new sheet of paper, preserving my original pattern. Then I decide where the lines to slash the pattern will be based on the positioning for these lines in standard grading procedure. I draw these cut lines on the pattern front and back.

Then, I align the pattern and the sloper at the low hip. This is mostly just personal preference – I like to orient my pattern work with the bony structure of the hip and then adjust around the softer, more shapeable parts of the body. Then I make vertical adjustments first by slashing and spreading at the horizontal slash lines.

If my sloper is as long as the desired length of the final pattern, I want to use the top and bottom of the sloper to define the general position of the top and bottom of my graded pattern. I tape the pattern pieces temporarily in position so they don’t slide around while I adjust further.

Then I look at the pattern horizontally. The sloper establishes the general position that I should slide my pattern pieces into. The pattern pieces will probably extend beyond the horizontal edges of the sloper, because the pattern will have additional ease added here to give it its shape.

The new position of the pattern pieces acts as a guide for where to redraw the seam lines for the enlarged pattern. The outer seam shapes should be traced over and smoothed from the pattern position after spreading apart, as shown by the red dotted lines above. The position of the inner seams can be determined mathematically if you choose by determining the proportions of the original and maintaining that proportion in the enlarged pattern. (I’m pretty comfortable with eyeballing it for simple patterns, though.)

Where there is design ease included in the pattern, it may be necessary to adjust to match the proportions of the original pattern. In this case, if I’m enlarging the pattern significantly, the amount of design ease at the bottom may need to be increased slightly to match the proportions of design ease to the body measurement of the original. I might add a bit more volume to the bottom flare to keep the look of the pattern consistent, as shown in the red lines above. If I’ve only graded up a size or two, this may not be necessary, though, since the difference in proportion would be relatively small.

Then I true the seams by comparing the seamlines to make sure the lengths of all of my seams match up, redraft any facings or waistbands using the new pattern pieces as my guide, and add back seam allowances. My final results would look something like the yellow pattern pieces below:

Grading a Pattern Down Using a Sloper

Decreasing pattern size is a similar process, but pieces will be overlapped instead of spread apart. In this case, I have a pattern that is too large, and a sloper that is my desired size.

First I trace the pattern onto a new sheet of paper, preserving my original pattern. Then I decide where the lines to slash the pattern will be based on the positioning for these lines in standard grading procedure. I draw these cut lines on the pattern front and back.

Then, I align the pattern and the sloper at the low hip. Then I make vertical adjustments first by slashing the pattern at the horizontal slash lines and overlapping to align it with the top and bottom of the sloper. I tape the pattern pieces temporarily in position so they don’t slide around while I adjust further.

Then I look at the pattern horizontally. The sloper establishes the general position that I should slide my pattern pieces into. The pattern pieces will probably extend beyond the horizontal edges of the sloper, because the pattern will have additional ease added here to give it its shape.

The new position of the pattern pieces acts as a guide for where to redraw the seam lines for the enlarged pattern. The outer seam shapes should be traced over and smoothed from the pattern position after overlapping, as shown by the red dotted lines below. The position of the inner seams can be determined mathematically if you choose by determining the proportions of the original and maintaining that proportion in the enlarged pattern. (I’m pretty comfortable with eyeballing it for simple patterns, though.)

Where there is design ease included in the pattern, it may be necessary to adjust to match the proportions of the original pattern. In this case, if I’m reducing the pattern significantly, the amount of design ease at the bottom may need to be reduced slightly to match the proportions of design ease to the body measurement of the original. I might remove some volume to the bottom flare to keep the look of the pattern consistent, as shown in the red lines above. If I’ve only graded down a size or two, this may not be necessary, though, since the difference in proportion would be relatively small.

Then I true the seams by comparing the seamlines to make sure the lengths of all of my seams match up, redraft any facings or waistbands using the new pattern pieces as my guide, and add back seam allowances. My final results would look something like the yellow pattern pieces below:

And that’s pretty much it for grading up and down with a skirt sloper. I hope this was helpful! Thanks again to the person who asked me about this process. If you have any questions about working with slopers, feel free to ask! And If you need a skirt sloper, I have several available at my Etsy shop here, including the stretch sloper pictured in the examples above. I hope everyone is safe and well and as contented as can be, given the craziness in the world at the moment.

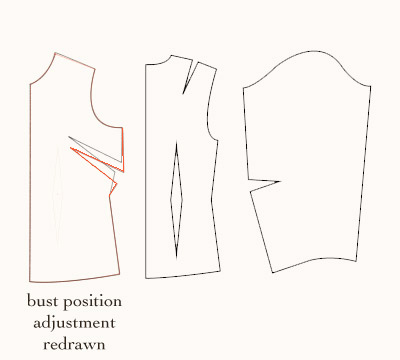

For the bust position, I measure the pattern from the high point shoulder to the bust point/apex/nipple, and the measurement is 9.5″. My actual body measurement is 10.5″, so for this area, I’m cutting the entire dart area out and shifting it 1″ lower and redrawing the side seam, and comparing to make sure the length still matches the back side seam length.

For the bust position, I measure the pattern from the high point shoulder to the bust point/apex/nipple, and the measurement is 9.5″. My actual body measurement is 10.5″, so for this area, I’m cutting the entire dart area out and shifting it 1″ lower and redrawing the side seam, and comparing to make sure the length still matches the back side seam length.